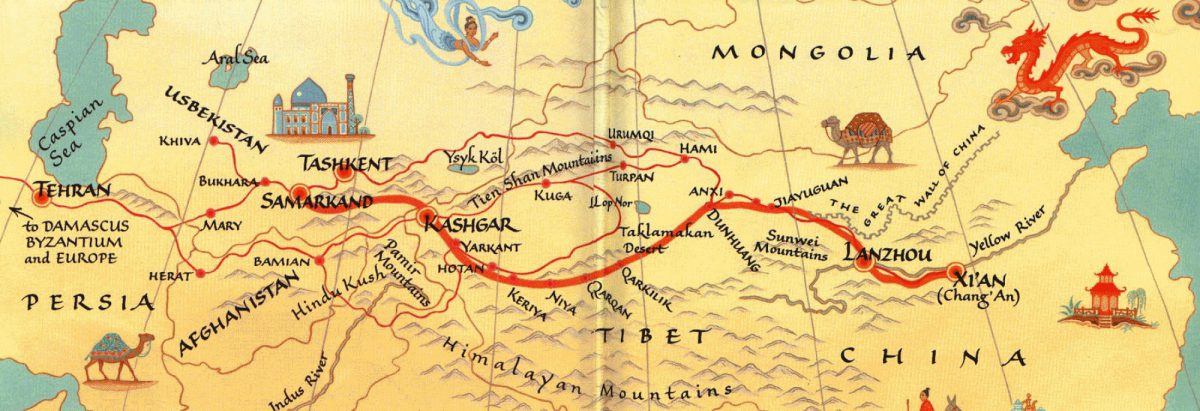

When the city was renamed Byzantium in the fourth century A.D.[1], the city of Constantinople, located in the heart of the eastern section of the then-Roman Empire, eventually came to be the urban capital of the Byzantine Empire. This capital of the Byzantine Empire played multiple roles in the kingdom, such as to house the emperor and produce agriculture, enough to partially sustain itself if the city ever came under siege.[2] Another integral role of the city was that Constantinople was an urban nexus of trade, connecting to cities both near and far. Constantinople played a crucial role in the sustainment of the Silk Road in the late Antique and Early Middle Ages, by both importing and exporting various coveted goods, as well as ideals, to and from other countries.

Various valuable goods and ideals moved in and out of Constantinople. These goods traded as far as up to hundreds of miles outside of the city walls of Constantinople, and passed through multiple countries. One type of coveted good that Constantinople moved was Christian relics, due to the prominence of Christianity within the city. Another valuable good that made its way into the borders of Constantinople was silk, and later leaders of the city tried to procure the means of producing silk. Christianity was exported out of the empire eastward, and reached as far as China. These different goods and ideals demonstrate the prominent role that Constantinople and the Byzantine Empire as a whole, had in the trade of the Silk Road.

The first type of good that moved its way both in and out of Constantinople was Christian relics. Constantinople, and the Byzantine Empire surrounding the city, were Christian societies. Christianity started to take hold in Constantinople when Constantine the Great of the Roman Empire issued the Edict of Milan in 312 A.D., which placed Christianity as the official state religion of the Roman Empire.[3] After the Byzantine Empire broke off from the Roman Empire, Christianity took root in the society of many of the cities, including Constantinople. Emperors started to place themselves in the center of the newfound ideology that took prominence within the Empire. Emperors centered themselves as a type of a “new David”[4], as a type of holy figure that legitimized the emperor’s power. These types of declarations helped to solidify the power of the emperor and cemented Christianity into the Byzantine Empire. When the city of Constantinople was attacked, people believed that the presence of holy relics of Christian figures (especially of the Virgin Mary) helped to protect them. Although a good number of these relics from the Virgin in Constantinople were more than likely fictitious in that the relics did not actually did not belong to the Virgin[5], people still believed in the saving power of the relics. During one siege on Constantinople, “the Virgin herself appeared to the people, brandishing her sword, encouraging the combatants and inspiring them to redden the waters of the imperial city with the blood.” [6] The inhabitants of Constantinople truly believed that keeping holy relics within their walls protected them.

This belief of divine protection from holy Christian figures consequently led to the desire to obtain more of these relics, most specifically from the holy land of Israel. Emperors took to retrieving relics of various places in the Middle East, such as Jerusalem. Items such as the “True Cross” were coveted after, and even after various wars with neighboring empires such as the Sassanid, who controlled these objects or the land that the holy objects remained in, a return with these relics resulted in a “triumph” and celebration.[7] Pilgrims made trips down to the holy land in search of relics, albeit for different reasons such as to relive moments that had been preached to them in a present sense. When the people of Constantinople were preached to in the present sense at Christian masses, these people gained stronger desires to relive the moments of the Christian liturgy by collecting relics and visiting holy lands.[8] Regardless, a desire for holy relics led the people of Constantinople to travel down to the Middle East to bring back holy relics with them.

The second good that moved in and out of Constantinople was silk. Like Christianity, the prominence of silk in the Byzantine Empire, specifically Constantinople, originated in the Roman Empire. The trade of silk from the Far East started with the Roman Empire, within which silk was quite fashionable. “Women from wealthy Roman families became … enamored with the silk crepe.”[9] People paid large sums of money to obtain silk, as silk was seen as a highly prestigious object. Silk remained a coveted object throughout the history of the Roman Empire.

As a result of this desire that originated within the Roman Empire, the people of Constantinople viewed silk as highly desirable. However, the purchase of silk was very costly for the Byzantines, as the “the only [land] supplier available to them was Persia whose prices were exorbitant.”[10] Silk purchases ultimately accounted for a large drain upon the Byzantine treasury. Eventually, the Byzantines tried to bring the means of production to within their own empire. The Romans were not able to find out how silk was produced and were forced to purchase silk from abroad. One scholar of the Roman world, Pliny the Elder, believed that the Chinese obtained silk from the trees in “their forests; after a soaking in water they comb off the white down of the leaves.”[11] Byzantine Emperors, such as Justinian I, brought monks from the Far East that carried “silkworm eggs, that they had managed to keep in good condition.”[12] With silkworms eggs, Constantinople, and the Byzantine Empire, as a whole were able to secure the means of producing silk, rather than purchasing silk for high prices. “Under Byzantine Emperor Justinian I, Constantinople became a center of silk production.”[13] Constantinople was able to internally produce silk for other sections of the Byzantine Empire

Finally, alongside these goods, Christianity was also exported out from Constantinople to places as far as China. One prominent division of Christianity that was exported out far east was Nestorian Christianity. During the early 5th century A.D. in the Byzantine Empire, a dispute arose over how Christ should be described. Two main competing viewpoints either described Christ as “two distinct persons, one human and one divine,”[14] or as one God that had always been singular. One prominent leader of the first viewpoint, Nestorius, was appointed Patriarch of Constantinople in 428 A.D.[15]. Nestorius taught the two-person viewpoint of Christ until he was driven out of Constantinople and banished to Egypt by leaders of the competing viewpoints, who ultimately won over the favor of the rulers of the Byzantine Empire.

Nestorian Christianity made its way to China in the 7th century A.D. over the routes of the Silk Road. However, the Nestorians did not win very many converts over to Christianity, as a Chinese census only listed around 3,000 Christians and Zoroastrians living in China during the Tang dynasty.[16] However, in 845 the Tang dynasty outlawed all foreign religions, including Nestorian Christianity, and by 980 a “Nestorian monk told a Muslim writer in Baghdad that he … had found no Christians surviving anywhere in the country [China].” [17] Regardless, Nestorian Christianity was a religion that was exported on the Silk Road by Constantinople.

So in conclusion, Constantinople, as well as the Byzantine Empire were prominent players in the Silk Road trade. Constantinople imported and exported various goods from afar, such as Christian holy relics and silk. These items were highly coveted after in the Byzantine world. Constantinople also exported Nestorian Christianity via the Silk Road, where Nestorian Christianity reached as far as China. However, Nestorian Christianity didn’t last long in some places in the east, as a Nestorian monk had reported seeing no traces of Christianity surviving within China during the mid-9th century. Other items such as alum and perfumes were also traded across the Silk Road from Constantinople.[18] All of these various goods and ideals demonstrate the integral role that Constantinople played in the Silk Road trade in the Late Antique and Early Middle Ages.

ENDNOTES:

[1] Peter Sarris, Byzantium: A Very Short Introduction. (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2015), 19

[2] Sarris, Byzantium, 25.

[3] Sarris, Byzantium, 14.

[4] Averil Cameron, “Images of Authority: Elites and Icons in Late Sixth-Century Byzantium.” Past & Present, no. 84 (1979): 21. http://www.jstor.org/stable/650535.

[5] John Wortley. “The Marian Relics at Constantinople.” Greek, Roman and Byzantine Studies 45,2 (Summer, 2005): 172. https://colorado.idm.oclc.org/login?url=http://search.proquest.com.colorado.idm.oclc.org/docview/229155399?accountid=14503.

[6] Cameron, “Images of Authority”, 5.

[7] Christopher I Beckwith, Empires of the Silk Road. (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press,2009), 120.

[8] Derek Kreuger, “Liturgical Time and Holy Land Reliquaries in Early Byzantium.” In Saints and Sacred Matter, edited by Cynthia Hahn and Holger A. Klein, 111-31. (Washington D.C.: Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection, 2015) 124.

[9] Xinru Liu, The Silk Roads: A Brief History with Documents. (Boston, MA: Bedford/St. Martin’s,2012), 9.

[10] Luce Boulnois and Bradley Mayhew, Silk Road: Monks, Warriors & Merchants on the Silk Road. (Hong Kong: Odyssey, 2004,) 229.

[11] Pliny. “Natural History.” In The Silk Roads: A Brief History with Documents, edited by Xinru Liu, 59-73. (Boston, MA: Bedford/St. Martin’s, 2012.) 60

[12] Boulnois and Mayhew, Silk Road: Monks, Warriors and Merchants, 232.

[13]Marian Vasile, “The Interplay Between Aesthetics, Silk, and Trade.”Geopolitics, History and International Relations 5, no. 1 (2013): 131. https://colorado.idm.oclc.org/login?url=http://search.proquest.com.colorado.idm.oclc.org/docview/1434867136?accountid=14503.

[14] Richard Foltz, Religions of the Silk Road: Premodern Patterns of Globalization. 2nd ed. (NewYork, NY: Palgrave Macmillan, 2010), 61.

[15] Foltz, Religions of the Silk Road, 61.

[16] Foltz, Religions of the Silk Road, 69.

[17] Foltz, Religions of the Silk Road, 70.

[18] Boulnois and Mayhew, Silk Road: Monks, Warriors and Merchants. 301.

Bibliography:

Beckwith, Christopher I. Empires of the Silk Road. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press,

Boulnois, Luce, and Bradley Mayhew. Silk Road: Monks, Warriors & Merchants on the Silk Road. Hong Kong: Odyssey, 2004.

Cameron, Averil. “Images of Authority: Elites and Icons in Late Sixth-Century Byzantium.” Past & Present, no. 84 (1979): 3-35. http://www.jstor.org/stable/650535.

Foltz, Richard. Religions of the Silk Road: Premodern Patterns of Globalization. 2nd ed. New York, NY: Palgrave Macmillan, 2010.

“Istanbul.” Unesco.org. Accessed October 1, 2016. http://en.unesco.org/silkroad/content/istanbul.

Khodadad, Rezakhani. “The Road That Never Was: The Silk Road and Trans-Eurasian

Exchange.” Comparative Studies of South Asia, Africa and the Middle East 30, no. 3 (2010): 420-33. Accessed September 28, 2016. http://muse.jhu.edu.colorado.idm.oclc.org/article/430307.

Kreuger, Derek. “Liturgical Time and Holy Land Reliquaries in Early Byzantium.” In Saints and Sacred Matter, edited by Cynthia Hahn and Holger A. Klein, 111-31. Washington D.C.: Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection, 2015.

Liu, Xinru. The Silk Roads: A Brief History with Documents. Boston, MA: Bedford/St. Martin’s,

“Map of Constantinople.” Digital image. Pininterest.com. Accessed October 1, 2016.

Pliny. “Natural History.” In The Silk Roads: A Brief History with Documents, edited by Xinru Liu, 59-73. Boston, MA: Bedford/St. Martin’s, 2012.

Sarris, Peter. Byzantium: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2015.

Waugh, Daniel C. “Constantinople/Istanbul.” Silk Road Seattle. 2004. Accessed October 1,

Wortley, John. “The Marian Relics at Constantinople.” Greek, Roman and Byzantine Studies 45, 2 (Summer, 2005): 171-187. https://colorado.idm.oclc.org/login?url=http://search.proquest.com.colorado.idm.oclc.org/docview/229155399?accountid=14503.

Vasile, Marian. “The Interplay Between Aesthetics, Silk, and Trade.”

Geopolitics, History and International Relations 5, no. 1 (2013): 130-135. https://colorado.idm.oclc.org/login?url=http://search.proquest.com.colorado.idm.oclc.org/docview/1434867136?accountid=14503.