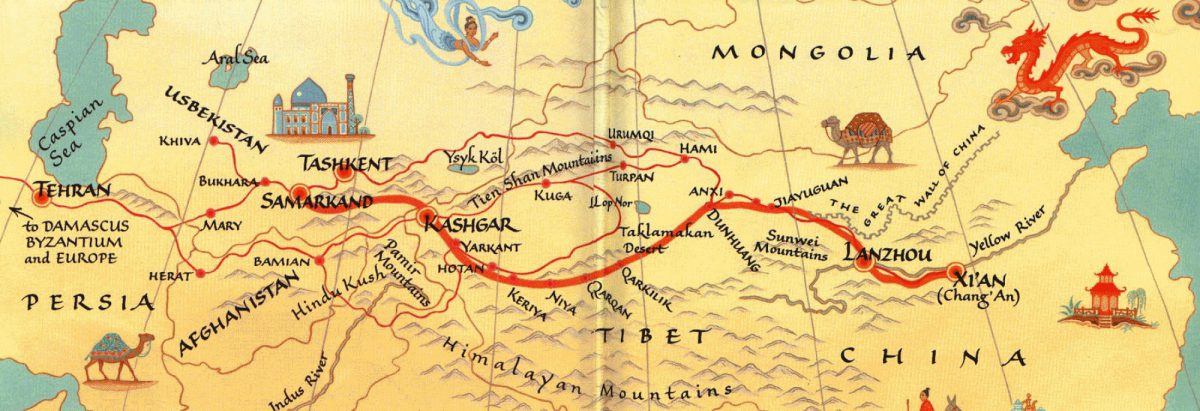

The Mongol invasion of Europe was one of the first large scale meetings between the Mongolians and the Europeans. Europeans accused the Mongol adversary of “eating human breasts, carrying out multiple rapes, skewering babies, slaughtering enough in Poland to fill nine large bags of ears, before leaving Hungary ‘drowned in blood’.”[1] After the Mongols left, most Europeans believed that they would return.[2] In an effort to curtail any further attacks on Europe, “the new pope, Innocent IV, fearing further onslaught on western Europe, sent two Franciscans, Lawrence of Portugal and John of Plano Carpini.”[3] These two envoys were both assigned with the task of seeing whether or not the Khan could be converted over to Christianity.[4] The latter of the two envoys, John, “was sixty-five years old, fat, and had no foreign language,”[5] but he became the “the first western envoy to travel all the way to Mongolia-the heartland and capital of the vast Eurasian Mongol Empire,”[6] assisted by a translator named Brother Benedict the Pole.[7] Friar John opened up diplomatic communications between the papacy and the Mongolian Empire. During his travels, the Friar also composed an account of the Mongols and the lands that he traveled through, which helped to dispel preconceived notions that were rampant within European society. Through his travels on the Silk Road, Friar John of Plano Carpini shaped interactions between the Mongolian Empire and the West as well as helped to shape Western notions of the Mongols.

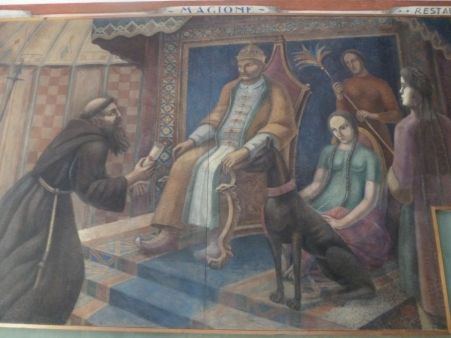

Friar John of Plano Carpini was the first western envoy to reach the heart of the Mongol kingdom, and was able to open up diplomatic communications with the Mongolians. On his journey, the Friar carried with him a letter intended for the leader of the Mongols from Pope Innocent IV, which begged the Mongols to “desist entirely from assaults … and especially from the persecutions of Christians.”[8] Initially, the friar traveled to the court of Sartak, a great Mongol leader, but Sartak “sent them without delay to his father the great Batu.”[9] However, Batu ultimately sent John of Plano Carpini to the Great Khan Guyuk, and “thanks to relentless haste they arrived at the camp of Karakorum on July 22nd.”[10] The Friar was greeted with a warm reception at the Great Khan’s court.[11] Eventually, Friar John of Plano Carpini transmitted the letter to Guyuk, and asked if the Khan would be willing to submit to Christianity. The Khan gave a less than favorable answer with a letter sent back to Pope Innocent IV, which commanded the Pope that “now you should say with a sincere heart: ‘I will submit and serve you’.”[12] Guyuk Khan agreed to submit to Christianity, but only if Pope Innocent IV would submit to him.[13] Even though this interaction between Pope Innocent IV and Guyuk Khan did not go smoothly, the interaction was one of the first between the Western Christendom and the Mongolian Empire.

In addition to establishing connections between the western and Mongolian worlds, Friar John of Plano Carpini helped to dispel earlier notions of what the Mongolians and the Eastern part of the world was like. This was achieved in part by the composition of the Friar’s travels, and on his return, “Carpini’s account eventually spread widely, turning the friar into a celebrity back home.”[14] Carpini’s account of his travels helped to dispel many old myths, as “the Christian West still accepted many old classical myths and legends about far off places and peoples and still tried to find a Biblical explanation and/or niche for everything and everyone.”[15] Some example of these myths were those that surrounded the Mongolian Empire. Historians of the time reported that “‘In the year 1240 a detestable nation of Satan, to wit, the countless army of the Tartars, broke loose … They are inhuman and beastly, rather monsters than men, thirsting for and drinking blood’.”[16] Alongside the myths surrounding the Mongols, other prominent myths about the kingdoms and lands to the far east existed. During the medieval ages, “many prominent scholars … describe[d] paradise as a real place on earth.”[17] A widespread notion prevailed at the time that one could travel to paradise, or the Garden of Eden, and it existed in the east. Medieval rumors also existed of a far off Christian king in the east. “In the 12th century, a legend spread across Europe of an empire ruled by a mighty Christian king and Priest named John and located somewhere in the East.”[18] The Friar was not above these legends either, as he wrote in his prologue to “History of the Mongols” that “‘we feared that we might be killed by that Tartars’.”[19] These legends and myths permeated medieval European society.

Through his account, Friar John of Plano Carpini dispelled these widespread notions of the peoples and the lands to the east. In his account “History of the Mongols”, the Friar gives the Mongolians human characteristics and demonstrates that they are not monsters. The Friar notes that the Mongols “are broader than other people between the eyes and across the cheekbones. Their cheeks are also rather prominent above their jaws; they have a flat and small nose, their eyes are little and their eyelids are raised up to their eyebrows.”[20] While the description is not flattering, it gives the Mongols humanistic characteristics. Carpini also praises some aspects of Mongolian daily life, noting that “fights, brawls, wounding, murder are never met among them.”[21] These descriptions immediately put to rest earlier conceptions of the Mongols. Friar John of Plano Carpini also casts doubt on earlier conceptions regarding other kingdoms and lands to the east. The Friar’s account makes no reference to an encounter with Paradise at all[22], and “Carpini only mentions Prestor John in his description of the rise to power of the Mongol Empire.”[23] Carpini’s account of his travels helped to dispel wide held notions of the east and the people living there in medieval times.

Furthermore, Friar John of Plano Carpini’s account helped Western powers in potential strategic maneuvering against the Mongols. Carpini’s “account provided strategic information to the pope and the West about the mysterious lands of the Mongols.”[24] “History of the Mongols” was full of information regarding the land between the West and the Mongolian kingdom. “Carpini surveyed the terrain for potential vulnerabilities in case of a pending crusade.”[25] This role of Friar John of Plano Carpini shows how cautious the West was with the threat of another possible Mongolian invasion.

In conclusion, Friar John of Plano Carpini played numerous important roles in his trip to the Mongolian heartland to meet the Great Khan Guyuk. Not only was the Friar the first western envoy to travel all the way to the Great Khan’s court, but he also composed an account of his travels to the court of the people and things that he saw along the way. Friar John of Plano Carpini’s account helped to dispel earlier notions of monstrous Mongols that were prominent in Medieval Europe, as his account gave them distinctly human features. His account also casts doubts on other notions that existed in medieval times, such as how Paradise laid to the east, and that there was a powerful Christian king named John living in the east. Furthermore, the account also helped the West in any potential strategic maneuvering against the Mongols, as the account provided a detailed description of the lands that Friar John of Plano Carpini rode through. The Friar was both an early diplomat to the Mongolian Court, and his account played multiple roles for western society.

The Importance and a Short History of the Friar:

Friar John of Plano Carpini, “who derives his name from Piano di Carpini near Perugia, was a man of ripe age who had taken a leading part in the establishment of the Franciscan Order in Western Europe”[26] by the time Pope Innocent IV was choosing who to send as envoys to the leader of the Mongols. John of Plano Carpini also followed heavily in his master’s footsteps, and “like his master, St. Francis, it was his wish to win converts for the Christian faith and this was his aim with respect to the Khan, although his prime task was to act as a Papal envoy.”[27] Carpini began his journey in Lyon with his interpreter Benedict of Poland in 1245, carrying a letter from the Pope that begged the Mongols not to attack the Christian world.[28] Eventually the Friar reached the Khan, attempted to convince him to convert to Christianity, but it didn’t work. Even though Carpini’s interactions with Guyuk did not go exactly as planned, the mission helped to establish relations between the West and the Mongols. Carpini’s account of his travels also helped to relay important information back to the West, such as the realities of the east that were in contrast to preconceived notions, and strategic information that could be used against the Mongols.

Works Cited:

Benedict the Pole. “The Narrative of Brother Benedict the Pole.” In Mission to Asia, edited by Christopher Dawson, 79-86. New York, NY: Harper and Row, 1966.

Dawson, Christopher. “Introduction.” In Mission to Asia, edited by Christopher Dawson, VII-XXXV. New York, NY: Harper and Row, 1966.

“First Europeans Traveled to Khan’s Court.” The Silk-Road Foundation. Accessed November 29, 2016. http://www.silk-road.com/artl/carrub.shtml.

Giffney, Noreen. “Monstrous Mongols.” Postmedieval 3, no. 2 (Summer, 2012): 227-245. doi:http://dx.doi.org.colorado.idm.oclc.org/10.1057/pmed.2012.10. https://colorado.idm.oclc.org/login?url=http://search.proquest.com.colorado.idm.oclc.org/docview/1016795433?accountid=14503.

Gillman, Ian, and Hans-Joachim Klimkeit. Christians in Asia before 1500. Ann Arbor, MI:University of Michigan Press, 1999.

Guzman, Gregory G. “European Clerical Envoys to the Mongols: Reports of Western Merchants

in Eastern Europe and Central Asia, 1231–1255.” Journal of Medieval History 22, no. 1(1996): 53-67. January 3, 2012. Accessed November 29, 2016. http://www-tandfonline-com.colorado.idm.oclc.org/doi/abs/10.1016/0304-4181(96)00008-5.

Guzman, Gregory. “Christian Europe and Mongol Asia: First Medieval Intercultural Contact between East and West.” Essays in Medieval Studies. 2002. Accessed November 29, 2016. http://www.illinoismedieval.org/ems/emsv2.html.

John of Plano Carpini. “History of the Mongols.” In Mission to Asia, edited by Christopher Dawson, 2-76. New York, NY: Harper and Row, 1966.

Lattimore, Owen, and Eleanor Holgate Lattimore. Silks, Spices, and Empire: Asia Seen through the Eyes of Its Discoverers. New York, New York: Delacorte Press, 1968.

Montalbano, Kathryn A. “Misunderstanding the Mongols: Intercultural Communication in Three Thirteenth-Century Franciscan Travel Accounts.” Information & Culture 50, no. 4 (2015): 588-610. doi:http://dx.doi.org.colorado.idm.oclc.org/10.7560/IC50406. https://colorado.idm.oclc.org/login?url=http://search.proquest.com.colorado.idm.oclc.org/docview/1726778486?accountid=14503.

Sherwood, Merriam, and Harold Elmer Mantz. The Road to Cathay. New York, NY: Macmillan Company, 1928.

The Friar at the Great Khan’s Court. Digital image. Eventieagre.it. August 28, 2012. Accessed December 3, 2016. http://www.eventiesagre.it/Eventi_Culturali/21049599_Anniversario dalla morte di Fra Giovanni da Pian del Carpine.html.

“The Mongols’ Mark on Global History.” The Mongols in World History. 2004. Accessed November 29, 2016. http://afe.easia.columbia.edu/mongols/history/history3.htm.

Valtrova, Jana. “Beyond the Horizons of Legends: Traditional Imagery and Direct Experience in Medieval Accounts of Asia.” Numen 57, no. 2 (2010): 154-85. Accessed December 2, 2016. http://www.jstor.org/stable/27793840

ENDNOTES:

[1] Noreen Giffney. “Monstrous Mongols.” Postmedieval 3, no. 2 (Summer, 2012): 231. doi:http://dx.doi.org.colorado.idm.oclc.org/10.1057/pmed.2012.10. https://colorado.idm.oclc.org/login?url=http://search.proquest.com.colorado.idm.oclc.org/docview/1016795433?accountid=14503.

[2] Gregory Guzman. “Christian Europe and Mongol Asia: First Medieval Intercultural Contact between East and West.” Essays in Medieval Studies. 2002. Accessed November 29, 2016. http://www.illinoismedieval.org/ems/emsv2.html.

[3] Owen Lattimore and Eleanor Holgate Lattimore. Silks, Spices, and Empire: Asia Seen through the Eyes of Its Discoverers. (New York, New York: Delacorte Press, 1968.), 61.

[4] Merriam Sherwood and Harold Elmer Mantz. The Road to Cathay. (New York, NY: Macmillan Company, 1928.), 5.

[5] Owen Lattimore and Eleanor Lattimore. Silks, Spices, and Empire. 61.

[6] Gregory G. Guzman. “European Clerical Envoys to the Mongols: Reports of Western Merchants in Eastern Europe and Central Asia, 1231–1255.” Journal of Medieval History 22, no. 1 (1996): 58. January 3, 2012. Accessed November 29, 2016. http://www-tandfonline-com.colorado.idm.oclc.org/doi/abs/10.1016/0304-4181(96)00008-5.

[7] Benedict the Pole. “The Narrative of Brother Benedict the Pole.” In Mission to Asia, edited by Christopher Dawson. (New York, NY: Harper and Row, 1966.) 79.

[8] John of Plano Carpini. “History of the Mongols.” In Mission to Asia, edited by Christopher Dawson. (New York, NY: Harper and Row, 1966), 76.

[9] Christopher Dawson. “Introduction.” In Mission to Asia, edited by Christopher Dawson (New York, NY: Harper and Row, 1966.) XVI.

[10] Dawson, “Introduction”, XVI-XVII.

[11] “The Mongols’ Mark on Global History.” The Mongols in World History. 2004. Accessed November 29, 2016. http://afe.easia.columbia.edu/mongols/history/history3.htm.

[12] Benedict, “The Narrative of Brother Benedict”, 86.

[13] “First Europeans Traveled to Khan’s Court.” Silk-road.com. Accessed November 29, 2016. http://www.silk-road.com/artl/carrub.shtml.

[14]Kathryn A. Montalbano “Misunderstanding the Mongols: Intercultural Communication in Three Thirteenth-Century Franciscan Travel Accounts.” Information & Culture 50, no. 4 (2015): 590. doi:http://dx.doi.org.colorado.idm.oclc.org/10.7560/IC50406. https://colorado.idm.oclc.org/login?url=http://search.proquest.com.colorado.idm.oclc.org/docview/1726778486?accountid=14503.

[15] Guzman, “Christian Europe and Mongol Asia”

[16] Sherwood and Mentz, The Road to Cathay, 2-3.

[17] Jana Valtrova. “Beyond the Horizons of Legends: Traditional Imagery and Direct Experience in Medieval Accounts of Asia.” Numen 57, no. 2 (2010): 161. Accessed December 2, 2016. http://www.jstor.org/stable/27793840.

[18] Valtrova, “Beyond the Horizons”, 165.

[19] Ian Gillman and Hans-Joachim Klimkeit. Christians in Asia before 1500. (Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press, 1999), 244.

[20] Carpini. “History of the Mongols”, 6.

[21] Carpini. “History of the Mongols”, 14-15.

[22] Valtrova, “Beyond the Horizons”, 162.

[23] Valtrova, “Beyond the Horizons”, 167.

[24] Montalbano, “Misunderstanding the Mongols”, 591.

[25] Montalbano, “Misunderstanding the Mongols”, 593.

[26] Dawson, Mission to Asia, n.p..

[27] Gillman and Klimkeit, Christians in Asia before 1500, 244.

[28] “First Europeans”, Silk-road.com.